Discovery, or background research, is something that happens at the beginning of the research process when you are just learning about a topic. It is a search for general information to get the big picture of a topic for exploration, ideas about subtopics and context for the actual focused research you will do later. It is also a time to build a list of distinctive, broad, narrow, and related search terms.

Learning Objectives

At the conclusion of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Search a library catalog to locate electronic and print books.

- Search databases to find scholarly articles, dissertations, and conference proceedings.

- Retrieve a copy or the full text of information sources

The words you use will help you locate existing literature on your topic, as well as topics that may be closely related to yours. There are two categories for these words:

- Keywords – the natural language terms we think of when we discuss and read about a topic

- Subject terms – the assigned vocabulary for a catalog or database

The words you use during both the initial and next stage of discovery should be recorded in some way throughout the literature search process. Additional terms will come to light as you read and as your question becomes more specific. You will want to keep track of those words and terms, as they will be useful in repeating your searches in additional databases, catalogs, and other repositories. Keeping a running list of these terms in Google Docs or a Word document will save you time later.

Discovery is an iterative process. There is not a straight, bright line from beginning to end. You will go back into the literature throughout the writing process as you uncover gaps in the evidence and as additional questions arise.

Finding scholarly articles

While books and ebooks provide good background information on your topic, the main body of the literature in your research area will be found in academic journals. Scholarly journals are the main forum for research publication. Unlike books and professional magazines that may comment or summarize research findings, articles in scholarly journals are written by a researcher or research team. These authors will report in detail the original study findings and will include the data used. Articles in academic journals also go through a screening or peer-review process before publication, implying a higher level of quality and reliability. For the most current, authoritative information on a topic, scholars and researchers look to the published, scholarly literature.

Many library databases have refining options that allow you to limit your search results to peer-reviewed.

Citation searches

Another way to find additional books and articles on your topic is to mine the reference lists of books and articles you already found. By tracing literature cited in published titles, you not only add to your understanding of the scholarly conversation about your research topic but also enrich your own literature search.

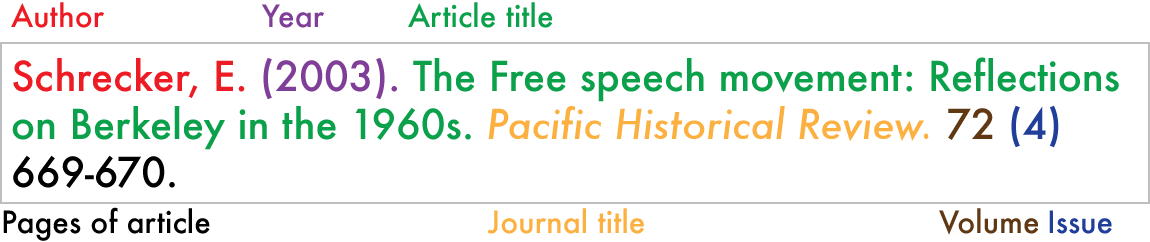

A citation is a reference to an item that gives you enough information to identify and find it again if necessary. You can use the citations in the material you found to lead you to other resources. Generally, citations include four elements:

- Author

- Title

- Source

- Date

For example,

For a good summary of how to read a citation for a book, book chapter, and journal article in both APA and MLA format, see this explanation at: https://www.slideshare.net/opensunytextbooks/gathering-components-of-a-citation

Finding conference papers

Conference papers are often overlooked because they can be difficult to locate in full-text. Sometimes the papers from an annual proceeding are treated like an individual book, or a single special issue of a journal. Sometimes the papers from a conference are not published and must be requested from the original author. Despite publication inconsistency, conference papers may be the first place a scholar presents important findings and, as such, are relevant to your own research. Places to look for conference papers:

WorldCat

- use keywords from the conference name (NOT the article title)

- it often helps to leave out terms like: conference, proceedings, transactions, congresses, symposia/symposium, exposition, workshop or meeting

- include the year of the conference

- include the city in which the conference took place

Google Scholar

- Search by keyword and add the word ‘conference’ and the year to your search, for example: ‘conference education 2008′

Note: If you utilize Google Scholar at any point, you can make it more useful by using the library links tool to establish a connection to the Reed Library catalog. This will inform you when an item in the results is available through Reed Library.

Here is a very quick video [00:36] to help you sync Google Scholar settings with Reed Library:

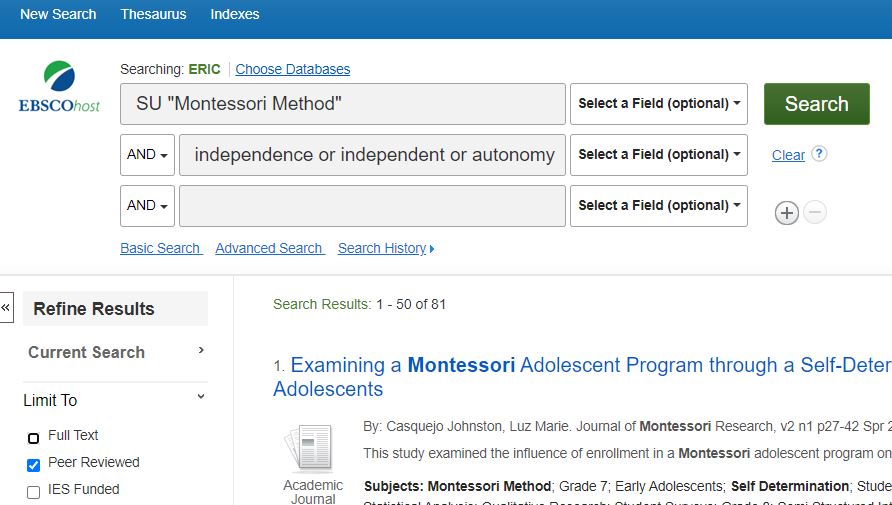

Databases

- For Education: ERIC, limit to ‘Collected Works–Proceedings’ or ‘Speeches/Meeting papers’

- For Allied Health/Nursing: CINAHL, limit to proceedings in the “Publication Type” box

- PsychInfo: limit to ‘Conference Proceedings’ in the “Record Type” Box

- Web of Science: limit to ‘conference’

Professional Societies & Other Sponsoring Organizations

Check the websites of the organizations that sponsor conferences. Listings of conference proceedings are often under a “Publications” or “Meetings” tab/link. The National Library of Medicine maintains a conference proceedings subject guide for health-related national and international conferences. Though many papers/proceedings are not available for free, the organization web site will often contain citations of proceedings that you can request through interlibrary loan.

Advanced searching

Now that you have an idea of some of the places to look for information on your research topic and the form that information takes (books, ebooks, journals, conference papers, and dissertations), it’s time to consider not only how to use the specialized resources for your discipline but how to get the most out of those resources. To do a graduate-level literature review and find everything published on your topic, advanced search and retrieval skills are needed.

Search Operators

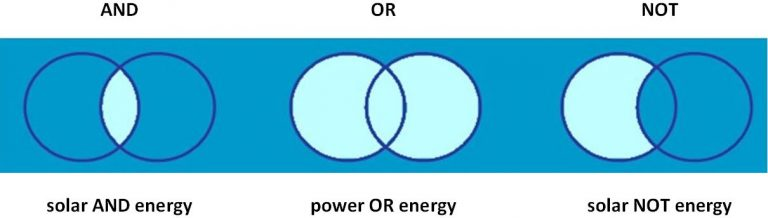

Literature review research often necessitates the use of Boolean operators to combine keywords. The operators – AND, OR, and NOT — are powerful tools for searching in a database or search engine. By using a combination of terms and one or more Boolean operators, you can focus your search and narrow your search results to a more specific area than a basic keyword search allows.

Boolean operators – allow you to combine your search terms using the keywords AND, OR and NOT. Look at the diagrams in Figure 4.6 to see how these terms will affect your results.

Truncation – If you use truncation (or wildcards), your search results will contain documents including variations of that term.

For example: light* will retrieve, of course, light, but also terms like: lighting, lightning, lighters and lights. Note that the truncation symbol varies depending on where you search. The most common truncation symbols are the asterisk (*) and question mark (?).

Phrase searching – Phrase searching is used to make sure your search retrieves a specific concept. For example “durable wood products” will retrieve more relevant documents than the same terms without quotation marks.

For a description of these more advanced search features, watch this short video [3:04] on effective search strategies.

Citation Searching

Citation searching works best when you already have relevant work that is on topic. From the document you identified as useful for your own literature review, you can either search citations forward or backward to gather additional resources. Cited reference searching and reference or bibliography mining are advanced search techniques that may also help generate new ideas as well as additional keywords and subject areas.

For cited reference searching, use Google Scholar or library databases such as Web of Science. These tools trace citations forward to link to newly published books, journal articles, book chapters, and reports that were written after the document you found. Through cited reference searching, you may also locate works that have been cited numerous times, indicating what may be a seminal work in your field.

With citation mining, you will look at the references or works cited list in the resource you located to identify other relevant works. In this type of search, you will be tracing citations backward to find significant books, journal articles, book chapters, and reports that were written before the document you found.

Attribution

This chapter is an adaptation of Where to Find the Literature (from Literature Reviews for Education and Nursing Graduate Students) by Linda Frederiksen, and is used under a CC BY 4.0 license.